Frames for an unhinged moment

In search of better frames: How to think when the world stops making sense

Hello, my name is Bhuvan, and thanks for reading What the hell is happening?

This newsletter is deliberately messy. It's more of a permanent draft than a finished post. There are no conclusions, and if there are any, they're unintentional—because nobody has any bloody idea what's happening in the world.

Think of this as a frantic attempt to make sense of chaos by someone anxiously looking to the past, the future, and in every direction at once. In the vein of Hegel's dialectic, these are collections of frames where I try to find the thesis and antithesis, hoping (but not expecting) to stumble upon a synthesis.

This is, more than anything else, a desperate attempt to make sense.

I hope you enjoy it. If you don't, I honestly don't care—but I do hope you'll leave a nasty comment so I can get some engagement out of your disappointment. So please, feel free. And if you're especially annoyed and unimpressed by the quality of this thing, I dare you to leave a comment.

It is undeniable that we seem to be living in a moment where a lot of things are happening all at once. Things are starting to feel crazier than ever. It's almost as if the unsaid agreement everyone had to allocate quotas for craziness has ended, and now everyone can go nuts. If you don't agree with this, then you seem to have a different grasp of reality than I do or stronger delusions. To me, however, this feels like a particularly unhinged moment.

Whether we realize it or not, we all struggle to make sense of reality and, in doing so, rely on different tools. One undercooked thought I have is that our difficulty in making sense of reality is not because of ignorance, but rather from the poverty of frames.

What I mean is that it's not that most people aren't aware of what's happening in the world; it's that the existing ideas and concepts we use to make sense of the present are inadequate.

What are frames?

Think of frames as mental shortcuts, heuristics, or very structured and context-rich lenses through which you process reality. They are like Instagram filters but for your thoughts. Frames are like midwives; they help you make sense of chaos.

Or, if I may use another metaphor, think of frames as LLM prompts. When you input a prompt into an LLM, it is processed through the collective intelligence of humanity. Frames are similar but vastly less ambitious in scope.

Some people call frames mental models, but I always hated that term because it's douchey!

The reason why I write this newsletter is to seek better frames. The challenge we all face is that things keep happening, and we all have to make sense of them in real time, and that's never easy. This is where frames come in handy. They help you get a quick and dirty sense of what's happening, enough to make reality tractable. Frames are like compression algorithms for reality.

We all use frames; we all have our favorite frames whether we realize it or not. Some popular frames are Occam's razor, inversion, black hat/white hat, the cyclicality of everything, map versus territory, role reversal, and Socratic questioning.

Metaphors are a classic example of frames. Metaphors are a figure of speech that can either help clarify or obscure meaning. By using a different reference, metaphors can often clarify complex situations.

The downside of relying on frames is that they can be crude and reductive. The reason why frames can be helpful in making sense of things is because they strip away the nuance and complexity and, in doing so, make things digestible. Having said that, you can never truly understand anything unless you grapple with the deep nuances and contradictions that are inherent in the events that shape our world.

So frames are like training wheels; they get your brain moving, but after that you need different tools to go deeper.

Why am I spouting all this crap, you ask, dear reader?

For one, I have a newsletter. If not spouting crap, what do you expect from a newsletter? The second reason is because I came across a recent podcast of historian Adam Tooze in which he speaks about "polycrisis" among other things. Then I got fascinated and heard another lecture of his. Ever since I read his book Crashed many years ago, I've been a fan of Tooze and his writing. He's one of the most thoughtful and perceptive thinkers and commentators about the challenges that beset humanity.

Anyway, the term "polycrisis" was first coined by French philosopher Edgar Morin and was later popularized in 2016 by Jean-Claude Juncker, the former President of the European Commission, to describe the simultaneous crises like the refugee crisis, Ukraine conflict, and populism that plagued Europe at that point.

Tooze uses "polycrisis" as a shorthand to describe the series of interlocking and overlapping crises across politics, geopolitics, health, climate, and economics.

A polycrisis is not just a situation where you face multiple crises. It is a situation like that mapped in the risk matrix, where the whole is even more dangerous than the sum of the parts. — Adam Tooze/Chartbook

I think polycrisis is a brilliant frame for thinking about the confounding moment we are all living through where everything seems to be happening all at once. Tooze's use of the concept is much like my own use of frames—it's a quick and dirty heuristic**,** and I think a valuable one at that.

The reason why I like the concept of polycrisis is that it immediately conveys the gravity of a moment where we are dealing with several existential challenges all at the same time.

Polycrisis for me is not the key term that does the analytical work—it's more a reminder of the fact that this is the challenge. The term is not in and of itself of much content at all. Where did I get it from? Jean-Claude Juncker, God help us, was tossing this concept around. So it's almost a kind of found object type approach—like Duchamp's urinal. Hey, this might be our condition, is the kind of gesture he's using.

At this point, don't we at least have to acknowledge that this is the kind of world that we're in? And it's a standing reminder to me. I've described it also, and I live it—I feel I hope—as a kind of practice of self-destabilization. Like any given day, in any given moment: am I facing, are we facing, is this thinking that we're engaged in facing the true destabilization of concepts and realities that we have to deal with?

It's what you'd say is a... it's an earworm. It's something that digs into you and goes 'this is awkward—how on earth can I be using this term?' It's that kind of provocation. It's the sand in the oyster. It's that kind of jarring idea."

A passage from an old post in which he wrote about the analytical inadequacy of the concept:

If stabilizing an account of overdetermination is difficult in practice, then to keep those radical and unsettling possibilities in mind we need irritating ideas that provoke non-essentializing thoughts. This heuristic is the best justification, it seems to me, for evoking irritating and incomplete concepts like “polycrisis”.

Polycrisis is underspecified. It is a weak theory. But those who criticize that in the name of greater clarity or stronger theory underestimate the scale of the mess that we are in. Polycrisis is useful precisely because it reminds us of the knowledge crisis, the gap between inherited critical theory and the radicalism of our present.

Polycrisis is underspecified. It is a weak theory. But those who criticize that in the name of greater clarity or stronger theory underestimate the scale of the mess that we are in. Polycrisis is useful precisely because it reminds us of the knowledge crisis, the gap between inherited critical theory and the radicalism of our present.

This kind of thinking is necessarily going to feel provisional and mobile and unsatisfactory. This is precisely what one expects from non-essentializing accounts that cannot and don’t want to offer the certainty of resolution/conclusion/category etc. They are on the move, rootless and, to a degree, fugitive.

I agree. As far as concepts that can galvanize our attention and get us to focus on the enormity of the present go, it's brilliant—it's a brilliant frame. Tooze in one of the podcasts describes it as a "found object." Having said that, it's still inadequate to coherently describe the jarring ways in which the crises that we are dealing with interact with one another in unpredictable ways.

The other thing that stood out to me in the podcast was Tooze's argument that we can't rely on inherited theoretical frameworks to make sense of the present. He goes on to say that we must be like magpie birds. Magpies are opportunistic scavengers that will collect whatever catches their eye, regardless of where it comes from, grabbing anything that seems useful:

The fundamental challenge of dealing critically with modernity is to keep up with the pace of change. Where do we get the conceptual armature to deal with this challenge? I take it to be a really profound problem—not one that can be fixed by modifying some pre-existing theory, and we can't have any confidence at all that the classical traditions of critical theory inherited from the 19th century provide us with the tools that we need.

Instead—and I've been watching Stuart Hall videos a lot recently, I taught 'Policing the Crisis' this term—I find in him precisely this kind of relentless focus: our problem is not to rehash existing theory. Our problem is to be at least as smart as the conjuncture, and that will involve a kind of magpie activity of desperately appropriating whatever handles we have for understanding the world that might be there.

This I take to be the gesture of Marx as well in the 1850s. Where do you go? You take scraps of British political economy and German philosophy and patch them together, and it's all pretty much of-the-moment stuff. Marx doesn't really have a deep classical tradition to draw on in putting those things together, and we shouldn't pretend to ourselves that we do now.

Having said that, polycrisis for me is not the key term that does that analytical work—it's more a reminder of the fact that this is the challenge. The term is not in and of itself of much content at all.

I think without the ability to be an intellectual itinerant and scavenger, one will have a tough time making sense of the utterly crazy moment we are all in.

The structural transformation of global finance

Hyun Song Shin is the head of the Monetary and Economic Department at the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) and is one of the smartest observers of global finance. His research is mandatory reading in my book and is indispensable for understanding global finance.

He recently gave a talk about the structural changes to the global financial system after the global financial crisis, and it was fascinating. His talk revolved around the rise of shadow banks, the centrality of sovereign bonds in finance, and the growth of foreign exchange swaps (FX swaps), among other things.

Watching the talk made me think about just how much of global finance is hidden or in the shadows. Most people equate financial markets with stocks, bonds, derivatives, and commodities like gold, but these are just the sexy things. Beneath the global financial system, hidden from view, is a financial system of gargantuan proportions and nightmarish complexity that enables the intermediation of trillions of dollars in value.

We only hear about parts of this hidden system whenever something goes wrong—like the recent yen carry trade blowup or a crisis like 2008. But to my mind, one can't really understand how finance works without a basic understanding of this hidden side of the global financial markets. For that, reading the research that the good people at BIS publish is indispensable. Their research is also highly underrated.

Anyway, the talk was super insightful, and I want to share some highlights:

The 2008 global financial crisis was a watershed moment for the global financial system. It led to a profound shift in the structure of the US financial system and, by extension, the rest of the world as well. The first major shift was the decline of banks and the rise of non-banking financial intermediaries.

In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 COVID crisis, issuance of government bonds increased dramatically. Where did all the bonds end up? A lot of them ended up on the balance sheets of banks and institutional investors.

After 2008, regulations curtailed US banks from a lot of lending activities and instead forced them to hold a lot of "safe" government securities. At the same time, institutional investors like pension funds, insurance companies, and asset managers grew dramatically in size and became increasingly hungry for liquid, high-grade assets like government bonds.

Large institutional investors like pension funds and insurance companies have to diversify globally and can't just load up on domestic bonds. Many of them, like Japanese and Taiwanese insurers, have become massive holders of US sovereign bonds, among others. While US bonds are "safe," there's a currency risk.

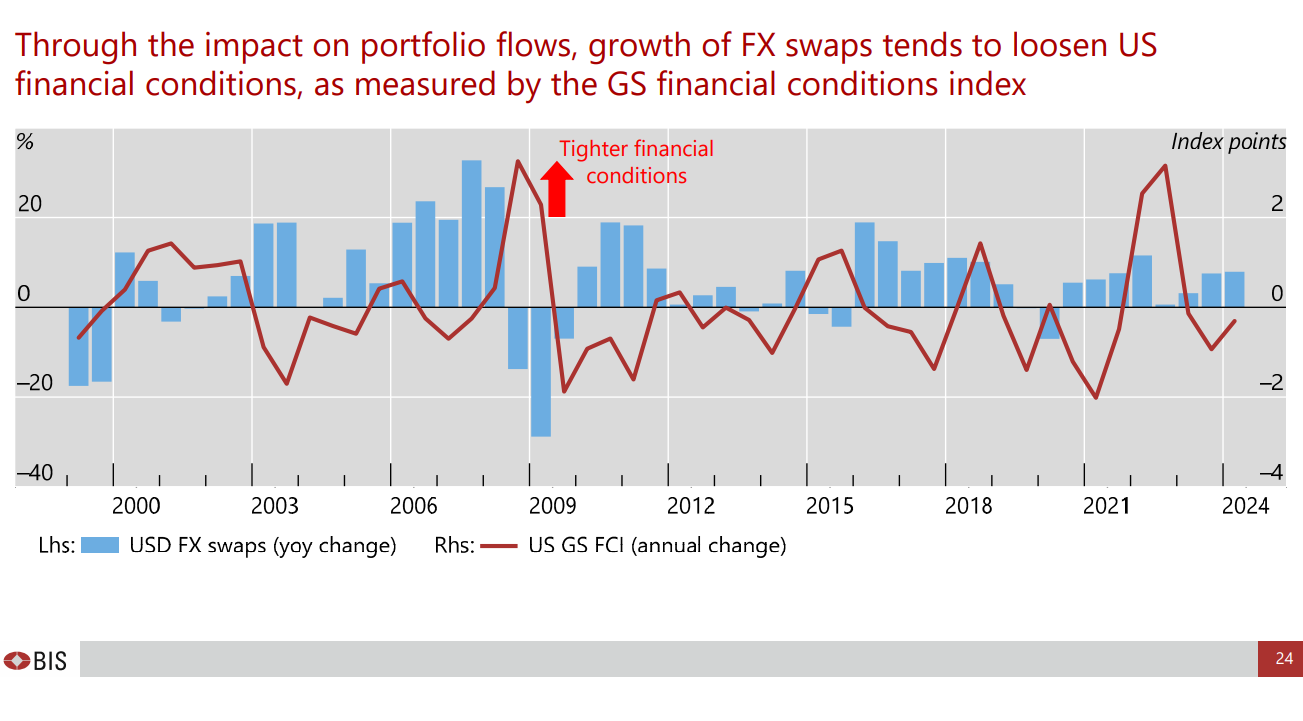

This currency mismatch has led to the spectacular growth of the foreign exchange swap market, where these institutions can hedge their currency exposures.

Foreign exchange swaps are one of the largest and least understood markets in global finance. At $113 trillion in outstanding notional value, this market is bigger than virtually every other asset class. A lot of these are hidden off-balance-sheet transactions that are hidden from traditional regulatory monitoring systems.

FX swap markets are not just mere passive conduits for global capital flows but rather key nodes that amplify risk. When investors are optimistic and willing to take risks, they increase their use of FX swaps to access global markets, which in turn affects financial conditions through portfolio flow channels.

If you want to understand events like the recent yen carry trade blowup, it's important to understand how swap markets work and how they are structured. While traditional banking statistics showed relatively modest yen lending of around $250 billion, the FX swap data showed something different. Yen-denominated swaps were roughly 50 times larger than on-balance-sheet lending.

Thanks to the growing importance of swap markets, the nature of risk transmission has transformed. This dynamic was evident during the March 2020 COVID crisis, when global investors faced a "scramble for dollars" as they rushed to meet their FX swap obligations without selling their underlying bond holdings at fire-sale prices. The Federal Reserve's expansion of central bank swap lines was partly a response to this development, providing an alternative source of dollar liquidity when private markets seized up.

During periods of stress like COVID or the recent yen carry trade blowup, there can often be "post-hoc hedging" where unhedged investors rush to hedge their currency exposures, which creates a self-reinforcing cycle of sharp moves in not just currencies but also stocks and bonds due to deleveraging.

All these shifts complicate life for financial regulators. All the tools used to stabilize the financial system in the aftermath of the global financial crisis—higher bank capital requirements, stress tests, enhanced supervision—were bank-focused. But when $113 trillion in activity operates off-balance-sheet through non-banks, those tools become largely irrelevant. What the growth of the FX swaps market shows is that regulators have to "unlearn" some lessons from the global financial crisis, as Shin says.

A few charts:

The twilight of humans?

There are two ways of dealing with artificial intelligence (AI):

Just ignore that AI even exists and live life normally until AI does something to you.

Try to make sense of it.

Option one is easy and requires no mental effort, but I wouldn't recommend it. Ignorance is bliss until an AI robot quietly walks behind you and violates you. Then it's not bliss anymore. It will hurt.

Option two is a nightmare but is non-negotiable in my view. You should try to understand AI not because you'll find answers about what it can or cannot do. At the very least, you'll learn how to ask better questions.

Also, assuming that trying to make sense of artificial intelligence is anything but a nightmare will be a very costly mistake. The reality is that even people who work in artificial intelligence labs don't really understand what they are building. They don't know how the thing they built works. They don't know what it will do to humanity. This makes understanding these technologies—even by listening to the people building them—that much harder.

Making sense of the alien technology that is artificial intelligence is not going to be easy. At this point, for the layperson, AI is indistinguishable from magic and sorcery. When something feels like magic, it becomes even harder to predict its trajectory or prepare for its impact. Magic doesn't follow rules we can extrapolate from.

Going back to the point I made earlier about using frames, the frame I use to think about artificial intelligence is to assume disruption by default.

What do I mean by that?

I would rather operate with the starting assumption that artificial intelligence will fundamentally reshape our world and humanity. Rather than stick my head in the sand and assume that it is the median mediocrity of humanity or a statistical party trick or a statistical bullshitter. I'm ignoring the doom and gloom and instead taking a middle path. I'd rather not really agree with the doomers or the boosters, but assume a reasonable but substantial impact of these technologies.

We also suffer from a poverty of language. Or rather, imprecise language in trying to describe these technologies. We often attribute mental qualities and states like "intelligence," "consciousness," "thinks," "believes," and "intends" to these systems. But we have no clear evidence these systems actually possess the internal experiences these words typically describe.

When we use words like consciousness, intelligence, understanding, and reasoning, we may be anthropomorphizing the machines. We're projecting our human-built model of representing and understanding the world onto a large language model that fundamentally may or may not have the same world model as us.

Having said that, at this point, if you assume that these technologies will not have any major impact on society, based on the evidence of the capabilities we've seen, you must be really high on some drugs that were spiked. Or you have some strong delusions that I'm incapable of conjuring.

Why I Like the Disruption by Default Frame

The first reason I personally like the disruption by default frame is because it's liberating. Assuming that most things will be fundamentally reshaped has kind of helped me get rid of my anxiety. In a very real Stoic sense, it is making peace with the fact of the worst-case outcome and trying to think clearly about what I can do. Or rather, what are my possibilities.

You might ask on what basis I am assuming disruption?

Plain old linear extrapolation—like dragging a bunch of Excel cells to autofill them.

I am assuming that AI progress will continue at its current pace. Do I have any evidence for this? Absolutely not. But then, who else does?

If anybody else claims to have a very fancy statistical model about the rate of progress of AI, they're talking out of the wrong opening of their body**,** which should in most cases remain shut until certain times either at the beginning of the day or end of the day.

And let's be honest: if most of us are extrapolating, our models for extrapolation are pretty much sci-fi movies, sci-fi novels, and just plain old imagination. To assume or even delude oneself into thinking that one has better or more robust models would be a lie of the highest order.

Assuming disruption by default is one way of thinking about it. But I think it's also important, if one is really thinking about how to make it in this possibly brave new world that is slowly creeping upon us, to look for other frames, other more robust frames. It is important to look for other views and opinions, some of which might be outlandish, weird, discomforting, and some anxiety-inducing, just plain nightmares.

And I think the task before us is not to bury our heads in our hands. It is actually to make an intellectually honest effort to seek out widely different perspectives**,** so that you have a sense of the range of possibilities or potential futures that one might have to deal with. That is what I am doing in this post—presenting different and opposing perspectives.

In some real sense, I can't help but shake the feeling that in the age of artificial intelligence, our very humanity is up for renegotiation. We might have to question the very things that make us human.

If artificial intelligence is going to take away our jobs, we will be losing a strong anchor that is probably the only source of meaning for a lot of people. For most people, whether it's good or bad, their entire identity and source of meaning revolves around the work they do. If an artificial intelligence bot or agent is going to take that job, where will humans find meaning?

I swear I didn’t copy this from Tyler Cowen but he dropped this banger in a recent article:

We stand at the threshold of perhaps the most profound identity crisis humanity has ever faced. As AI systems increasingly match or exceed our cognitive abilities, we’re witnessing the twilight of human intellectual supremacy—a position we’ve held unchallenged for our entire existence. This transformation won’t arrive in some distant future; it’s unfolding now, reshaping not just our economy but our very understanding of what it means to be human beings.

We are not doomers; quite the opposite. One of us, Tyler, is a heavy user of this technology, and the other, Avital, is working at Anthropic (the company that makes Claude) to usher it into the world.

Both of us have an intense conviction that this technology can usher in an age of human flourishing the likes of which we have never seen before. But we are equally convinced that progress will usher in a crisis about what it is to be human at all.

Our children and grandchildren will face a profound challenge: how to live meaningful lives in a world where they are no longer the smartest and most capable entities in it. To put it another way, they will have to figure out how to prevent AI from demoralizing them. But it is not just our descendants who will face the issue, it is increasingly obvious that we do, too.

The other classic example where the debate about whether AI is good or bad is playing out: education. Recently, there was a New York Magazine article about how ChatGPT is being used by students to engage in mass plagiarism. The article quoted several experts who had very differing views.

Troy Jollimore, a poet, philosopher, and Cal State Chico ethics professor, has concerns. “Massive numbers of students are going to emerge from university with degrees, and into the workforce, who are essentially illiterate,” he said. “Both in the literal sense and in the sense of being historically illiterate and having no knowledge of their own culture, much less anyone else’s.” That future may arrive sooner than expected when you consider what a short window college really is. Already, roughly half of all undergrads have never experienced college without easy access to generative AI. “We’re talking about an entire generation of learning perhaps significantly undermined here,” said Green, the Santa Clara tech ethicist. “It’s short-circuiting the learning process, and it’s happening fast.”

On the doomer side, some of the experts were lamenting the fact that students are willingly signing up to outsource their thought to the machines. To be a student, to learn**,** and to write an essay is to engage with the act of learning, which is often frustrating and equally rewarding.

It is to think deeply about a subject, to engage with a vast body of literature, views, opinions, and research about that particular topic, then form one's own views about that particular topic, then transform that understanding into words. It is equally frustrating and equally rewarding. But today, this entire intellectual wrestling match is just one chat prompt away in a sterile little white box that is threatening the very essence of what it is to be human.

Then, on the booster side of artificial intelligence, you have people who say things more or less like: The genie is out of the bottle, and there's no really putting it back. If students are really using tools like ChatGPT and Claude to "cheat" through their assignments and essays, there's no real way to stop that because it's physically impossible.

This means some people are of the view that what teachers should be really doing is teaching students how to use these tools instead of being sticklers—instead of being spoilsports trying to catch out cheaters. The job of a teacher now is to teach students how to get the exact same thing that they were getting in the pre-ChatGPT world in the post-ChatGPT world.

Academic, essayist and professor

summarized the predicament facing colleges succinctly in a brilliant essay recently :The usual, comfortable rhetoric about “irreplaceable” human elements of education—mentorship, hands-on learning, community building, and critical thinking—might suffice for a four-year social networking summer camp, and some parents may still value that. But in the AGI era, the only defensible reason for universities to remain in operation is to offer students an opportunity to learn from faculty whose expertise surpasses current AI. Nothing else makes sense.

Marketing that touts traditional benefits of a university education while ignoring AGI actively harms the sector, suggesting that higher education either fails to grasp the AGI revolution or is trying to hide from it. Universities must instead lead with brutal honesty: students should pay precisely for the “last mile” of human knowledge that surpasses AGI’s capabilities. The true value of a university lies in faculty who can offer advanced education, mentorship, and inspiration at the highest level, while every other aspect of college life becomes a secondary consideration that no longer justifies tuition on its own.

—

Every faculty member should begin to write a detailed memo specifying the following: “What specific knowledge do I possess that AGI does not? What unique insights or capabilities can I offer that exceed AGI systems? Which students, and in which topics, would benefit enough to pay to learn from me and why?” Faculty who cannot produce this memo with concrete, defensible answers have no place in the institution. There is no middle ground.

Author and teacher Jonathan Malesic critiques the hype around AI in education, arguing that ChatGPT and similar tools are fundamentally "gimmicks" rather than revolutionary educational tools:

Ted Hadzi-Antich’s students read and discussed these words by James Baldwin: “Perhaps the whole root of our trouble, the human trouble, is that we will sacrifice all the beauty of our lives, will imprison ourselves in totems, taboos, crosses, blood sacrifices, steeples, races, mosques, armies, flags, nations” —I might add technologies and hype bubbles—“in order to deny the fact of death, which is the only fact we have.”

Part of a teacher’s job—certainly in the humanities, but even in professional fields like business—is to help students break out of their prisons, at least for an hour, so they can see and enhance the beauty of their own minds. It is to help them learn, together, to defend how they want to live, precisely because they, too, unlike a machine, will one day die.

I will sacrifice some length of my days to add depth to another person’s experience of the rest of theirs. Many did this for me. The work is slow. Its results often go unseen for years. But it is no gimmick.

Ok, this is sad and funny at the same time:

Here’s how

plans to deal with students using ChatGPT to cheat:You never learn ideas as well as when you have to write about them. That’s why I have my students write ten very short take-home essays, due each Friday afternoon after they’ve spent the week reading the material and discussing it in class—with me, the graduate students who lead their discussion sections, and each other. Most find these “shorties” difficult at first, but they appreciate them by the end of the semester.

Now, of course, ChatGPT can crank out shorties in seconds.

I think I can reconcile the two models of teaching though. Next semester, I’m going to keep the shorties but make them worth much less (20%) leading to two in-class exams that carry more weight (60%) in which students write the same kind of short essay they’ve been writing all semester. In theory, those who write the shorties themselves will perform better on the exams than those who outsource to ChatGPT. If essays really do teach students how to write and think, then we should be willing to design our courses on that principle.

Some students will accept the rationale but gamble anyway—when other coursework is pressing or social opportunities entice.

It's AI & humans, not AI vs. humans. Fascinating article on how Mayo Clinic is using artificial intelligence across radiology, cardiology and other fields:

That’s true for radiologists at the Mayo Clinic, one of the nation’s premier medical systems, whose main campus is in Rochester, Minn. There, in recent years, they have begun using A.I. to sharpen images, automate routine tasks, identify medical abnormalities and predict disease. A.I. can also serve as “a second set of eyes.”

“But would it replace radiologists? We didn’t think so,” said Dr. Matthew Callstrom, the Mayo Clinic’s chair of radiology, recalling the 2016 prediction. “We knew how hard it is and all that is involved.”

Lawyers are using LLMs to look for citations and the LLMs are hallucinating making up nonexistent cases:

It's been two years since the first widely publicized incident of this, which I wrote about at the time in Lawyer cites fake cases invented by ChatGPT, judge is not amused. At the time I naively assumed:

I have a suspicion that this particular story is going to spread far and wide, and in doing so will hopefully inoculate a lot of lawyers and other professionals against making similar mistakes.

Damien's database has 116 cases from 12 different countries: United States, Israel, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, Brazil, Netherlands, Italy, Ireland, Spain, South Africa, Trinidad & Tobago.

20 of those cases happened just this month, May 2025!

Dario Amodei, CEO of Anthropic, is predicting apocalypse:

AI could wipe out half of all entry-level white-collar jobs — and spike unemployment to 10-20% in the next one to five years, Amodei told us in an interview from his San Francisco office.

Amodei said AI companies and government need to stop "sugar-coating" what's coming: the possible mass elimination of jobs across technology, finance, law, consulting and other white-collar professions, especially entry-level gigs.

Why it matters: Amodei, 42, who's building the very technology he predicts could reorder society overnight, said he's speaking out in hopes of jarring government and fellow AI companies into preparing — and protecting — the nation.

Is Dario right? Is the jobs crisis here already?

Duolingo announced plans this week to replace contractors with AI and become an “AI-first” company — a move that journalist Brian Merchant pointed to as a sign that the AI jobs crisis “is here, now.”

In fact, Merchant spoke to a former Duolingo contractor who said this isn’t even a new policy. The company cut around 10% of its contractor workforce at the end of 2023, and Merchant said there was another round of cuts in October 2024. In both cases, contractors (first translators, then writers) were replaced with AI.

Merchant also noted reporting in The Atlantic about the unusually high unemployment rate for recent college graduates. One explanation? Companies might be replacing entry-level white-collar jobs with AI, or their spending on AI might simply be “crowding out” the spending for new hires.

The defining question of our time:

CEOs are using avatars of themselves in earnings calls:

CEOs are now so immersed in AI, they’re sending their avatars to address quarterly earnings calls instead of themselves, at least partially.

After the Klarna CEO’s AI avatar appeared on an investor call earlier this week, Zoom CEO Eric Yuan followed suit, also using his avatar for initial comments. Yuan deployed his custom avatar via Zoom Clips, the company’s asynchronous video creation tool.

That’s it for this week. I have plenty of other things to share but I don’t want to be the reason you self-destruct.

Peeps, you still there? So what did you think about this issue?

It seems like constantly focusing on the economy in your recent market articles is creating a sense of unnecessary anxiety to this author. This kind of tone doesn't reflect the level of quality we've come to expect from Zerodha markets. (Maybe the author is due a long unwinding break 😉)

I’d strongly recommend reading Factfulness by Hans Rosling—it offers a more grounded perspective on global trends and could help clear up some of the anxiety behind your writing.

As for the AI wave, while it's getting attention, it's still far too inefficient to replace real work in fields like engineering, finance, and law. It will, however, improve human productivity, which seems to be the real takeaway.

Please reconsider the tone of these articles or make them a part of some other fearmongering series. They’re starting to dilute the quality Zerodha markets is known for.

Wow. Amazing waste of time. Please get a separate newsletter for this and not be a part of zerodha so that I don't have to unsubscribe to the whole of zerodha. TX