It’s AI’s world; we’re just living in it

On reasoning machines, debt trains, dumb trade wars, and why even cats are smarter than your chatbot.

Hello, my name is Bhuvan, and thanks for reading What the hell is happening?

This newsletter is deliberately messy. It's more of a permanent draft than a finished post. There are no conclusions, and if there are any, they're unintentional—because nobody has any idea what's happening in the world. Think of this as a frantic attempt to make sense of the unfolding chaos.

AI Is a Rorschach test

I wrote a little about how I think about AI in a previous post. Recently, I took a stab at thinking about what the rise of AI means for people’s personal finances. In writing about AI, what struck me is that it’s like a Rorschach test:

The Rorschach test is a psychological assessment where you look at inkblots and say what you see in them.

The idea is that since the inkblots are just random shapes, whatever you perceive reveals something about your personality, thoughts, or mental state. A psychologist analyzes your responses - what you see, where you focus, how you describe things - to gain insights into your psychological makeup.

It's based on the theory that people project their inner world onto ambiguous stimuli. Though widely known, its scientific validity is debated among psychologists.

One of the problems with all the debates around AI is that they are a bit like WWE matches. They look entertaining, but there’s no real substance. It seems to me like most people reason from a place of fear or ignorance, and both are unhelpful. It’s important to use these tools, follow the progress of these technologies, and then reason sensibly. We must all be good Bayesians.

wrote a brilliant post titled "All the ways I want the AI debate to be better" that reads like a frustrated teacher's attempt to restore order to a classroom that's devolved into shouting matches. He writes from the perspective of someone who's watched AI discussions become increasingly polarized and detached from reality and offers both a diagnosis of what's wrong with how we talk about AI and a prescription for fixing it.It’s a long post, and I’m still making my way through it, but I highly recommend reading it. This should be a foundational document that should be mandatory reading for people trying to grapple with how to make sense of AI.

I’m continuing my own AI sensemaking journey, and I watched two interviews of Yann LeCun, chief scientist of Meta AI. He has a much more measured take on the utility of LLMs and the pace of AI progress. A few takeaways from his two talks:

Today's AI models start to fall apart the longer they go on. Each word they generate comes with a bit of uncertainty, and over time those small errors snowball into nonsense. So while they can handle short tasks well, they struggle with complex problems that require sustained, step-by-step reasoning. Some experts believe this fundamental flaw means the current approach to building AI—what's called “autoregressive language modeling”—won’t get us very far in the long run.

But the deeper issue goes beyond language. If we want AI that actually thinks and interacts like a human or even like a cat, we have to teach it how the real world works. That’s not easy. The physical world is messy, unpredictable, and constantly changing. It’s far harder to model than structured language, which is why we still don’t have trustworthy home robots or fully autonomous cars. As Yann LeCun puts it, “We can’t even reproduce what a cat can do.”

Humans, especially children, learn by soaking up a constant stream of sights, sounds, textures, and movement. A toddler processes more sensory data in four years than what’s available in all the text on the internet. That’s where real learning about cause, effect, and the laws of nature comes from—not from reading, but from touching, seeing, and doing. LeCun argues that AI needs to learn the same way: through experience across multiple senses, not just by chewing through mountains of text.

To reason like us, machines need an internal model of the world, a kind of mental simulation engine. Just like a baby learns that things fall when dropped, or a cat plans its jump onto a ledge, AI will need to ask itself, “What happens if I do this?” That kind of thinking—predicting consequences and planning actions—is the foundation of real intelligence. Pattern-matching alone won’t get us there.

Another big hurdle is planning across layers. Humans naturally break big goals into smaller steps. If you're trying to get to Paris, you know you first need to get to the airport, call a cab, stand up, walk, and so on. Our brains handle these layers without much effort. AI, at the moment, can’t. That ability to think in steps, at different levels, is still missing, and cracking that problem is likely to be one of the major research frontiers over the next decade.

Finally, LeCun suggests we aim for something more grounded than AGI (artificial general intelligence). The term implies a kind of all-knowing superbrain, which is neither realistic nor useful. Human intelligence isn’t truly general—we’re just really good at the kinds of tasks that helped us survive and evolve. A better goal, he argues, is advanced machine intelligence: systems that can match or beat humans in specific areas that matter. Not gods. Just really good tools.

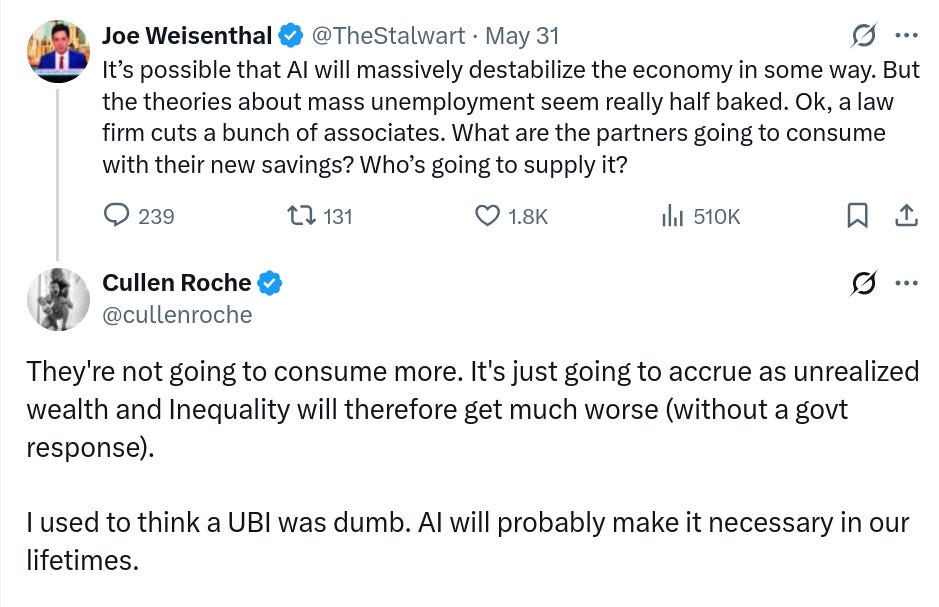

A thoughtful and sensible take by

Victor Kumar

on AI that aligns with my own:

An LLM gives you purchase not on isolated facts but on systems of knowledge distilled from its vast training material. With a little experience, you’ll learn that you can use this knowledge to interface with a world of facts. You don’t take ChatGPT’s outputs on trust. You use them—discovering their accuracy by seeing how they help you solve problems or elicit further knowledge from expert sources. That’s how ChatGPT helped me during my father’s medical crisis, but medicine is only one system of knowledge it can unlock.

I’m not here to declare ChatGPT an unalloyed good. Its benefits may be outweighed by producing cognitive torpor, fueling psychoses, and serving up slop. Rather, I just want to make the case that, if used wisely, it’s an invaluable tool. It may not help with your job, your art, or (uh) social companionship—I’m just talking everyday life management.

A new paper from Apple researchers was generating a lot of hot takes on Twitter for showing that AI models with "thinking" capabilities, like OpenAI's o1 and Claude's reasoning mode, have some pretty serious limitations.

The researchers got tired of testing these models on the same old math problems (which the AI might have already seen during training) and decided to create their own controlled experiments using classic puzzles like the Tower of Hanoi and river crossing problems. This way, they could increase the difficulty precisely and watch exactly where things went wrong.

Key findings:

Every reasoning model hits a hard wall where accuracy drops to zero once puzzles reach a certain complexity. For instance, models that could handle Tower of Hanoi with 8 disks would completely fail with 10+ disks, despite having plenty of computational resources available.

At low complexity, regular models without reasoning modes actually outperform and are more token-efficient than thinking models. At medium complexity, thinking models show clear advantages. But at high complexity, both approaches fail completely, suggesting there's an optimal "sweet spot" for when reasoning helps.

What's strange is that as the problems got harder, the AI models actually spent less time thinking. Even though they still had lots of computing power available, they used fewer “thinking tokens” on the tougher questions. That’s the opposite of what good reasoning should look like.

On simple puzzles, thinking models found the right answer quickly but then kept exploring wrong solutions for no reason. On difficult puzzles, they couldn't find any correct solutions at all, showing poor allocation of their reasoning effort.

A few interesting takes both for and against the conclusions in the paper:

Who is using AI to code? Global diffusion and impact of generative AI

A new study from researchers analyzed 80 million GitHub commits to track real-world AI coding adoption across countries. The study reveals dramatic differences in how the technology is spreading globally. Rather than relying on surveys or controlled experiments, researchers built an AI detector to identify machine-generated Python code in actual GitHub contributions from 200,000 developers worldwide (2018-2024).

So this is pretty fascinating. American developers are using AI tools the most, hitting 30% adoption. Germany and France are close behind at 24% and 23%. Indian developers started behind European countries but adopted AI rapidly from 2023, reaching 21.6% by 2024.

New GitHub users generate 41% AI code vs. 28% for veterans, potentially shrinking skill gaps between junior and senior developers.

30% AI usage correlates with 2.4% more code commits, translating to $9.6-14.4 billion in annual US value (potentially $64-96 billion with higher estimates).

AI users explore 2.2% more new libraries and 3.5% more library combinations, suggesting the technology expands developers' capabilities rather than just speed.

Share of AI-generated Python functions over time

I had more links related to AI, but I’ll share them next week.

Caveat: Assume that all research papers are blog posts and read them, and don’t assume they are gospel. This is a small mental hack I use because a lot of papers get debunked.

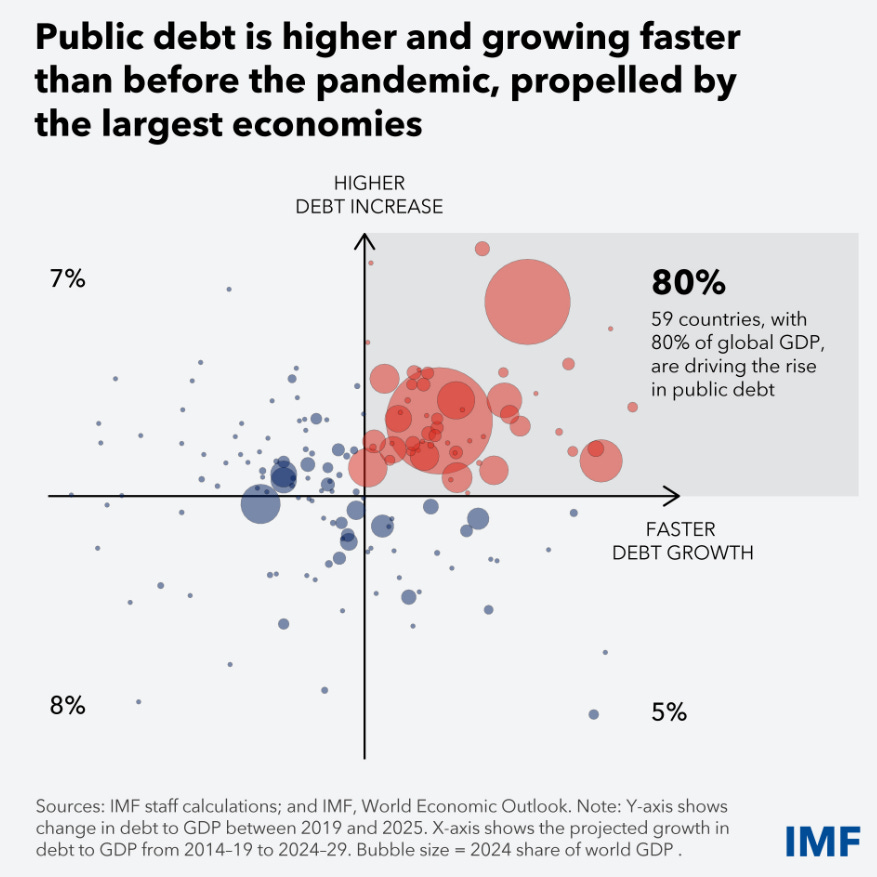

Nothing stops the debt train?

For decades we've been hearing about the coming debt crisis. I'm talking about since the 1980s, when economists were writing books with apocalyptic titles. Ed Yardeni, the guy who coined the term "bond vigilantes" back in 1983, recently pointed this out in a Bloomberg interview:

"Back in July of 1983 is when I concocted the term 'bond vigilantes.' I went back and read what I wrote, and I said the bond vigilantes are particularly upset about record $200 billion deficits. Here we are, looking at $2 trillion deficits and talking about the bond vigilantes once again."

Think about that for a second. $200 billion was considered apocalyptic in 1983. Now we're casually discussing $2 trillion deficits like it's Tuesday morning coffee talk.

The frame that's been operating for 40 years is this: governments can basically print money forever as long as interest rates stay low and nobody cares enough to demand higher yields. It's the financial equivalent of that Hemingway quote about going bankrupt—gradually, then suddenly.

What happens when things change?

I’m not saying that there’s a debt crisis happening, but something weird is happening. We're seeing a series of weak government bond auctions across developed economies that's making even seasoned market participants nervous.

Japan, South Korea, and Australia have all had weak bond auctions, and this is making people go, “Hmm, is the proverbial poop hitting the fan?”

Is this a crisis? Not yet, according to analysts at LSEG:

Recent increases in long government yields −JGBs particularly − are shown in Chart 1. A very weak 20 year JGB auction drove the spike amid reduced demand, and unrealized losses, from Japan life companies. But these companies have longer liabilities than assets, so increases in long yields improve net solvency, even if increasing unrealized JGB losses. So, this differs from 2023’s duration mismatch at US regional banks or self-feeding spiral in gilt yields in 2022, as pension funds de-leveraged. Also note long end yields above 5% are attracting LDI flows in the US and UK notably, as pension funds move into funding surpluses.

A longer-term contrarian perspective from the Financial Times:

Questions over demand for long-term sovereign debt have been exacerbated by an exodus of some of the more reliable buyers of this government paper. In the UK, traditional “defined benefit” workplace pension funds have mostly closed to new members and their existing members are ageing — meaning they have less need for long-term debt. Their place is increasingly being taken in the gilts market by hedge funds who want shorter-term bonds. A similar effect is playing out in Japan, where the country’s postwar baby boom generation is ageing and no longer needs the same level of long-term debt holdings, analysts say.

Here’s Ed Yardeni with a longer-term frame:

Well, higher yields should be bad, but they haven't been. We have seen a global bull market in stocks even though we've seen bond yields increase. My view is that, to a large extent, bond yields have normalized. They're back to where they should be. 4.5% is the right bond yield for the U.S. economy. That was the case before the great financial crisis, and I think it's the case again now. Maybe we're getting some excesses in the UK and some excesses in Japan, but if you want to be U.S.-centric, I think these bond yields are kind of normal.

However, I do see a risk that there could be a mini debt crisis, the way there was in 2023. And in some ways, Tom, I hope there is, because I think now's a good time for a debt crisis to get the attention of the politicians in Washington that they've got to get their act together.

What stops this train is unknown, or are we all MMTers now?

Given the spending required on defense, aging populations, energy transition, and so on, this is one long-term trend to watch for sure.

The stupid trade war

I’m loath to write about Trump’s dumb trade war, especially at a time when he’s having a schoolyard fight with Elon, but I can’t help it. There’s so much ridiculous crap happening that I can’t not talk about it.

Sorry.

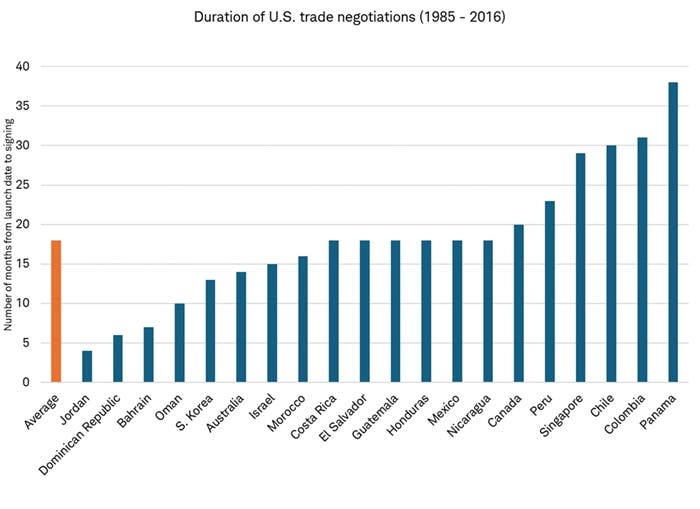

Remember the time when Trump aides said he would sign 90 trade deals in 90 days?

Well, he only has 89 to go!

The fact that it takes 18 months for the US to negotiate a trade deal is an alternate fact that has no bearing on reality!

But how are the trade negotiations going, you wonder?

Open disagreements, competition and confusion among Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick and U.S. Trade Representative Jamieson Greer have made it hard for the Japanese side to judge the Trump administration's intentions, according to sources close to the negotiations.

"At one point, the three cabinet officials put the talks with the Japanese side on hold and began debating right in front of them," said one source.

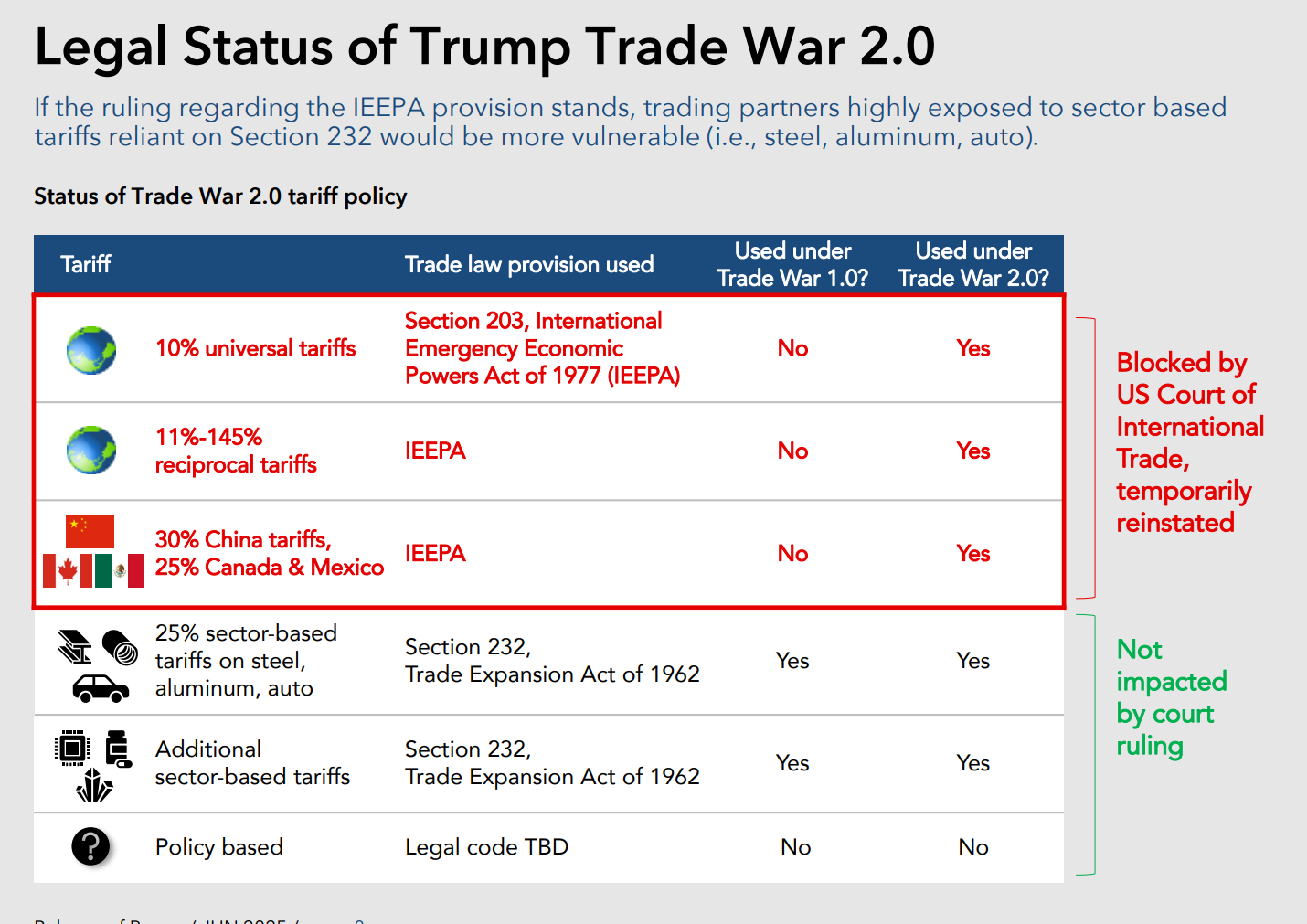

Despite the recent “pause,” tariffs are still extraordinarily high:

17.8%: The average effective U.S. tariff rate on imports, according to the Budget Lab at Yale. While the Trump administration has dialed back the threat of trade tariffs on China, Europe and other nations, the fact remains that, as of right now, the effective tariff rate on U.S. imports remains extraordinarily elevated. The tariff rate is roughly seven times higher than at the start of the year but remains in flux owing to the recent decision of the U.S. Court of International Trade, which ruled to strike down most of Trump’s new tariffs. So yes, the markets have adjusted to “Liberation Day”. But that said, we believe there is more market chop and churn coming due to higher U.S. tariff rates and the ensuing onus on U.S. firms to adjust.

Though the markets have moved on from the tariff war like a bad breakup, it doesn’t mean the drama is over:

The tariffs are starting to feed into prices. This data shows the prices of analysis now covers ~330,000 products across four major US retailers.

How are companies feeling right now, and how is the US manufacturing renaissance doing, you wonder?

Fantastically!

Several traditional and electric-vehicle makers—and their suppliers—are considering shifting some auto-parts manufacturing to China to avoid looming factory shutdowns, people familiar with the situation said.

Ideas under review include producing electric motors in Chinese factories or shipping made-in-America motors to China to have magnets installed. Moving production to China as a way to get around the export controls on rare-earth magnets could work because the restrictions only cover magnets, not finished parts, the people said.

If automakers end up shifting some production to China, it would amount to a remarkable outcome from a trade war initiated by President Trump with the intention of bringing manufacturing back to the U.S. — WSJ

Moving supply chains is not like moving furniture:

Processing rare earths is technically demanding, but China has developed new processes. Rare earth chemistry programs are offered in 39 universities across the country, while the United States has no similar programs.

China refines over 99 percent of the world’s supply of so-called heavy rare earths, which are the least common kinds of rare earths. Heavy rare earths are essential for making magnets that can resist the high temperatures and electrical fields found in cars, semiconductors and many other technologies. — NY Times

An interesting tweet thread on the lack of talent in the US

In the modern era, the key production factor that enables specialization is human capital. And a key (perhaps under-appreciated) component of Beijing’s policy approach is to take a *leading role in shaping how the country’s human capital is directed and allocated at a macro level, instead of relying as much on the free market (compared to Western countries).

Nice analysis by Carnegie on the impact of tariffs on a fragile Africa.

Trump's tariffs on Africa are causing a real mess. The crazy part is how uneven it all is. Some countries got hammered while others barely got touched. Lesotho, this tiny country in southern Africa, got slapped with a brutal 50% tariff rate, which is just insane. They built up this whole textile industry specifically to sell clothes to America, and now it's probably going to get wiped out. We're talking about 40,000 jobs, mostly women working in clothing factories.

Meanwhile, East African countries like Kenya and Egypt are sitting pretty with just the basic 10% tariff. They might actually come out ahead because their Asian competitors got hit way harder—Bangladesh is facing 37% tariffs, and Vietnam 46%. So while Kenya and Egypt are dealing with a small bump, their competition just got priced out of the market.

The timing is bad too. Africa's big trade deal with the US (AGOA) expires in September, and nobody knows if Trump's going to renew it. Without that, a lot of African countries lose their special access to American markets right when they're already getting hit with these new tariffs.

The pain isn't equal. Lesotho got destroyed with 50% tariffs, while East Africa mostly dodged the bullet with just 10%, showing how randomly these rates got assigned based on trade deficits

Africa's cash cows are safe. Oil, gold, copper, and other minerals that make up most of Africa's exports to the US are exempt, so the biggest exporters might not hurt as much as the numbers suggest

Unexpected winners. Kenya and Egypt could actually win big in textiles since their Asian competitors got hit with much worse tariffs, basically clearing the field for African producers

Finally working together. This crisis might be the kick Africa needed to stop relying so much on Western markets and start building real trade relationships with each other

Trade wars are chip wars

The other dimension of the US-China rivalry is the war over chips. The battle for semiconductor supremacy has been escalating steadily since 2018, picking up pace under Joe Biden in 2022.

🇺🇸🇨🇳 U.S.–China Chip War: A Timeline

2018: U.S. bans Fujian Jinhua over IP theft concerns.

2019: Huawei blacklisted (Entity List), cutting it off from U.S. tech.

2020: U.S. expands restrictions — foreign firms using U.S. tools can't supply Huawei; SMIC added to Entity List.

2022: Biden admin imposes sweeping export controls on advanced chips and semiconductor tools to China.

2023: Japan and Netherlands join U.S. in restricting chip equipment exports; China bans Micron chips in infrastructure; U.S. blacklists Chinese AI chipmakers (Biren, Moore Threads).

2024: U.S. tightens AI chip rules, expands restrictions on chip design software; China accelerates domestic semiconductor push.

2025: U.S. halts sales of EDA software, revokes visas for Chinese STEM students; China retaliates with rare earth export licenses.

— ChatGPT summary

This initial tariff-centric trade war has broadened into a comprehensive tech and supply chain conflict. The shift is due to a growing recognition in Washington and Beijing that technological leadership and national security are now joined at the hip.

The US-China rivalry is much more than trade deficits and surpluses. The focus has shifted beyond traditional goods to the foundational technologies and critical materials that underpin modern economies, such as semiconductors, artificial intelligence, and rare earth minerals. This is a profound transformation of the "trade war" into a multi-dimensional "tech war" and a "supply chain war," reflecting a deeper strategic rivalry.

As a result, China has worked hard to become technologically independent. Its "Made in China 2025" strategy aims to make the country self-sufficient and a leader in key advanced technologies, such as semiconductors, along the full value chain. Beijing has put a lot of money into local production, even though it has trouble with cutting-edge processes and relies too much on imports for now.

One interesting result of US export controls is that they encourage Chinese innovation, which seems counterintuitive. These rules are meant to limit China's progress and goals in technology, but Chinese companies have shown that they can adapt and come up with new ideas despite the rules. One example of this is the rise of Chinese large language models like DeepSeek, which were able to compete with American models even though they used a lot less computing power. As the old saying goes, "Necessity is the mother of invention," and, ironically, it makes me wonder how well US penalties will work in the long run to stop China from making AI progress.

A couple of weeks ago, the Trump administration escalated the chip war dramatically by banning the sale of American electronic design automation (EDA) software to China. EDA software is key to designing, simulating, verifying, and optimizing modern semiconductor chips. Creating advanced chips would be practically impossible due to their complexity without this software.

The ban is another move designed to cripple China’s progress in advanced semiconductor design, particularly for high-end chips used in AI and defense, by targeting a segment where US firms dominate the global market.

Will it work?

Probably not, even if we set aside the fact that enforcing the ban on software is much harder than enforcing the ban on physical chips:

To be sure, China has a long track record of resilience in the face of escalating sanctions. US President Donald Trump tried a similar trick in his first term when he blocked Huawei Technologies from accessing US technologies, including EDA software. Both Trump and Joe Biden introduced restrictions that curbed Chinese imports of mostly Japanese, American and Dutch chip manufacturing equipment.

Experts at the time said China would take years to come up with its own technologies. They did not expect Beijing to sponsor a US$47 billion fund to support indigenous equipment manufacturing. And they certainly did not anticipate DeepSeek, the Chinese AI model competing with OpenAI’s ChatGPT at a fraction of the cost.

Seven years after the initial ban, Huawei is a global force in smartphones and other areas. In April, Huawei announced its most powerful Ascend AI chip, which aims to compete with Nvidia’s earlier-generation technologies. — SCMP

All these bans will just boost China’s resolve to be self-sufficient.

Huawei, the Chinese tech group that has been under US sanctions since 2019, has invested heavily in developing its own EDA tools in its chip development work, as well as supporting local suppliers such as Empyrean to build alternatives. While these are not yet as mature as the products from EDA suppliers Synopsys or Cadence of the US, they are “usable”, especially for chip production at 7nm and above, say industry insiders.

Also read:

U.S. Restricts EDA Software Sales to China

Welcome to the new Cold War:

“The U.S. and China are in a state of economic decoupling and there do not seem to be any guardrails to prevent escalations in trade tensions from spreading to other areas,” said Rick Waters, a former senior U.S. diplomat who now runs the China center at the Carnegie Endowment for Global Peace. “It’s becoming more difficult to argue that we’re not in a new Cold War.”

“What we’re seeing now is the biggest trade war in history,” said Yun Sun, director of the China program at the Stimson Center, a Washington think tank. “The risk of the trade war expanding to other domains is quite high.”

Export controls are the new bullets:

Today, instead of warheads, the U.S. and China are wielding a range of new economic weapons that have the potential to cause widespread economic pain. Following the latest skirmish, China agreed to resume exports of rare-earth magnets and critical minerals needed by U.S. companies—but only for six months, The Wall Street Journal reported.

“If you look at traditional arms-control treaties, the primary goal was to prevent a catastrophic, worst-case scenario from materializing,” said Emily Benson, head of strategy at the advisory firm Minerva Technology Futures and a former Commerce Department official. “And that’s certainly what we see here in the economic domain.”

That’s it for this week. What did you think?

Great writing

Wow thank you so much for sharing and for the amazing feedback!