Hello, my name is Bhuvan, and thanks for reading What the hell is happening?

This newsletter is deliberately messy. It's more of a permanent draft than a finished post. There are no conclusions, and if there are any, they're unintentional—because nobody has any bloody idea what's happening in the world.

Think of this as a frantic attempt to make sense of chaos by someone anxiously looking to the past, the future, and in every direction at once. In the vein of Hegel's dialectic, these are collections of frames where I try to find the thesis and antithesis, hoping (but not expecting) to stumble upon a synthesis.

This is, more than anything else, a desperate attempt to make sense.

I hope you enjoy it. If you don't, I honestly don't care—but I do hope you'll leave a nasty comment so I can get some engagement out of your disappointment. So please, feel free. And if you're especially annoyed and unimpressed by the quality of this thing, I dare you to leave a comment.

Learning the wrong lessons from history

We are strange creatures. We almost always keep mentally time-traveling between the past and the future and spend very little time in the present. In these mental time travels, the past holds a special significance. The past, or history, is a guide, a sherpa with whose help we make sense of the present and try to grapple with the future. Whether we admit it or not, the futures we imagine are more often than not an extrapolation of the past, linear or otherwise.

Given this tendency, it's important to understand what history can tell us and, more importantly, what it can't. Unknowingly, we treat history as an oracle personified that has all the answers to the problems we face in the present. The other way of saying this, it's easy to learn the wrong lessons from history.

Why am I saying this?

Three reasons:

This feels like a unique moment in history when a lot of things are happening all at once. At the very least, many world-historic trends that have been in motion for a long time are converging all at once—and not in a good way. It's not the end of history that Fukuyama predicted but rather the metastasization of history. As all of this is happening, we are grappling for ideas and frames to make sense of the present.

I remembered something the historian Niall Ferguson said on a 2023 Davos panel with Ian Bremmer and Adam Tooze:

Niall Ferguson: Well, I have to confess I don't like the word polycrisis. Uh I'm I'm with Gideon Rachman on this. It makes me think of polystyrene and polyester, things I never much liked. And I'm also somewhat skeptical of geopolitical recession as a term. I mean, this is just history. It's just how history works.

During one of my doomscrolling sessions on YouTube, I came across a video by the eminent historian Margaret MacMillan on what history can teach us. I first came across her work when I was writing this post on the outbreak of WWI, and her books have been on my reading list ever since.

Margaret is brilliant, and the first video I watched was so good that I watched another old video of hers on a similar topic. I highly recommend watching her videos, but I want to share a few things that stuck with me.

The past can be helpful not to reassure us that everything is ok, but in helping us distinguish between what is new and what isn't. Our societies have dealt with the assaults on important institutions and values before as well. What history can do is help us not panic because most of the challenges we face aren't new.

History can help us gain a sense of humility because it reminds us we are not cleverer than the people in the past, and we don't always do things in a better way. History can help illuminate the range of possible solutions to our pressing problems. Perhaps most importantly, history helps us gain perspective.

History doesn't give us clear answers, nor does it help us predict the future. There's too much history, and one can always find a version to justify his or her beliefs about something. What it can do is help us understand who people are, where they come from, and what their stories are. It shrinks our ignorance and gives us perspective.

Without knowing history, we will never truly understand who we are. Without understanding who we are, where we come from, and how we got to where we are, we can never truly understand others. Without knowing the histories of other people, you can never truly understand who they are.

History is not an impartial judge. You need to understand history so that you can be skeptical of it.

Bad versions of history can be used to mobilize people and sow hatred among others. Knowing history can help us be vigilant against such misuse of history. It helps us question and challenge the dominant national narratives—often bad ones—that people organize based on.

History is like a warning sign. It can tell us that if we do X, we'll be in trouble. History is littered with the cautionary tales of powerful people and nations doing dumb and terrible things and biting the dust. It helps us see that there are alternatives and other ways of doing things.

While history doesn't give us answers, knowing the past can help us formulate better questions about what's happening in the present.

So, I think what history can do, and why I would like our leaders to know history, is that it can help us with warnings: "If you do this, you will get into trouble," or "You are likely

She also recently wrote a foreboding article on the decay of the international order, and this passage stood out to me:

As a historian, I study those moments in the past when an old order decays beyond the point of return and a new one emerges, but I never expected to live through one. I should have. Today’s world is lurching toward great-power rivalry, suspicion, and fear—an international order where the strong do what they will, as Thucydides wrote, and “the weak suffer what they must.” Imperialism, which never really disappeared, is back. Governments and think tanks now speak of spheres of influence, something the U.S. long opposed. If history is a guide, this will not be an easy or pleasant transition.

I’ll leave you with this from the awesome Joe Weisenthal of Bloomberg:

People love to say, “Those who do not learn history are doomed to repeat it.” But another relevant truth for investors is, “Those who learn their history are doomed to think it’s repeating.”

The stupid trade war

One of the readers commented on the first edition of this newsletter and said:

I am sure there must be some interesting economic story will be happening around the world as well apart from trade wars. No disrespect, I am big fan

I replied:

Haha, I get the frustration but this is the ONLY story that matters right now. The repercussions of this stupidity are insane. But point taken.

I get the reader's frustration, and I'm equally sick and tired of the stupidity of the trade war, but I'm still forced to pay attention to it because the repercussions are scary, to say the least. For some reason, I thought of this edition of the stupid trade war with this:

And this scene is from the awesome 30 Rock. Imagine Trump instead of Tina Fey shouting, “you’re tariffed, you’re tariffed.”

With that wonderful imagery now in your head, I must subject you to a few of the latest developments in the stupid trade war.

But before that, have you started feeling manly yet?

The big development, of course, is that this dumb charade seems to be slowly winding down. Trump agreed to reduce the tariffs to 30% for 90 days and China to 10% while both of them try to thrash out a “deal”:

The U.S. agreed to temporarily reduce tariffs on China to 30%, down from 145%. Beijing said it will lower tariffs on U.S. goods to 10% from 125%.

Trump said Monday morning that tariffs on China would not go back to 145%, even if a longer-term deal cannot be reached once the 90-day pause expires.

“But they would go up substantially,” Trump added.

The U.S. side of the temporary agreement shrinks Trump’s “reciprocal” tariffs on China to 10%. The U.S. is also maintaining 20% tariffs that were previously imposed over allegations about China’s role in bringing fentanyl to America.

The U.S. said it will additionally retain tariffs that were in place for specific Chinese products, including steel and aluminum, before early April.

Given the devastating impact of the tariffs on small businesses, the massive backlash even among die-hard MAGA supporters, the threat of a possible recession, and tanking approval ratings, this was to be expected, I guess. Trump overplayed his hand and had no choice but to walk back. Instead of US-China trade slowly grinding to a total halt, it'll now find a new equilibrium.

Economists agreed that the US might have overplayed its hand by raising the tariffs too quickly and too high. “The US blinked first,” said Alicia García-Herrero, chief Asia-Pacific economist at French investment bank Natixis. “It thought it could raise tariffs almost infinitely without being hurt, but that hasn’t been proven right.”

Alfredo Montufar-Helu, senior adviser to the China Center at the Conference Board think-tank in New York, said it would have been impossible for Chinese producers to offset the 145 per cent tariffs imposed by the US. “But at 30 per cent, I think most Chinese imports into the US would regain their competitiveness.” — FT

Even if tariffs were to remain at this level, they still represent a big hit and will push up prices on a vast swathe of goods.

This is funny and true.

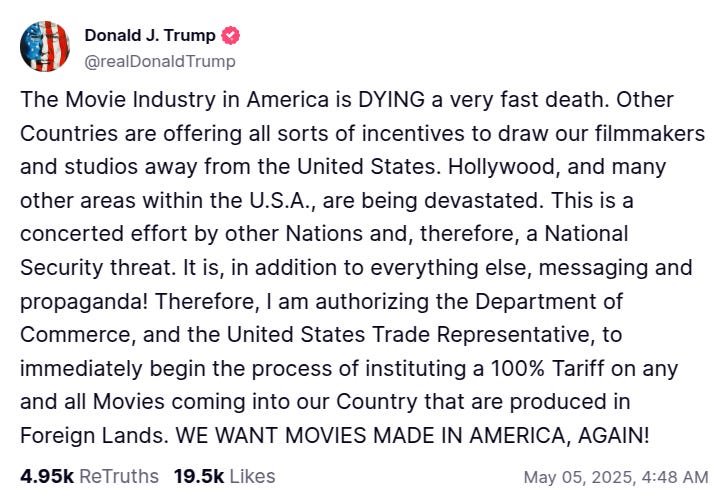

The other escalation in the stupid trade war is frankly a genius move: Trump wants to save Hollywood and is therefore imposing a 100% tariff on foreign movies. Awesome right?

Nobody has a clue about how the tariffs will be calculated. Will it be only on the scenes shot outside the US as a percentage of the total scenes? I wouldn't be surprised if a further 100% tariff was imposed on movie scenes with non-US actors. Screw Javier Bardem, Charlize Theron, Penélope Cruz, Hugh Jackman and Priyanka Chopra. They are, after all, immigrants stealing the roles that would've otherwise gone to honest and hard-working white people.

It takes a special brain that has been bathed in the corrosive fumes of McDonald’s Jumbo meals, gasoline fumes, and marinated in the high IQ visual art of Fox News to come up with this giga-brained move.

Here’s the irony, as pointed out by one user on Twitter (I ain’t calling it X):

Honestly, it’s hard to understand. Why does Trump keep doing things that harm his own country? The U.S. is the world’s number one exporter of movies. The more a country like that rejects foreign films, the more likely other countries are to watch fewer American movies. And naturally, that would hurt the success of American films as well.

This stupid tariff will hurt Indian cinema as well:

By the time RRR came thundering across Dolby screens in the American heartland in 2022, drawing midnight audiences who hadn’t heard the word “Tollywood” before, Indian cinema had become something of a Trojan horse in Hollywood’s backyard. RRR amassed approximately $14.9 million [Rs 124 crores] in North America, signalling a significant shift in the global cinematic landscape.

Now, with Trump 2.0 unveiling a 100% tariff on foreign-produced films, it looks like the horse is about to be torched at the gates. The announcement was made on May 5, 2025: a flat 100% tariff on all non-American films entering the U.S., citing “national security” and “the need to protect our great American film industry from foreign distortion.”

The irony, of course, is that America already dominates the global film market like no other, flooding territories with so much content that regional industries are forced into aesthetic compromise or extinction. What this tariff really threatens is not cultural infiltration, but cultural reciprocity—a shared oxygen of storytelling across borders. For Indian cinema—which in recent years earned over $100 million [Rs 840 crores] from US theatres alone—this is not just a bruise; it’s a gut punch.

European-style digital tax but for movies?

Foreign countries will seize Trump’s tariffs as justification for their home-grown measures to limit Hollywood offerings. Screen quotas and ticket taxes are obvious tools. Such measures are particularly likely in the Global South. The 100 percent tariff proposal not only ignores the huge overseas earnings of Hollywood films but also fails to appreciate America’s soft power generated by the movie industry. Citing just two hits, Barbie grossed $809 million outside the US and Oppenheimer grossed $644 million. While the North American film market is large, it is dwarfed by the huge international market. In the end, retaliation against Hollywood and related services could sharply reduce the $37 billion trade surplus enjoyed by the US entertainment industry overall.

Get ready for the whiplash

Note: I wrote this before the US decided to pause the tariffs for 90 days, but the logic still remains the same.

80% of international trade volumes move on the oceans. It's not a stretch to say that the oceanways are the arteries of global trade. When things move smoothly, that extra moisture-absorbing Gucci underwear you ordered arrives in time, and the regions down south of your abdomen remain comfortably dry. But if there's a small clot in even one of the arteries, then things go haywire.

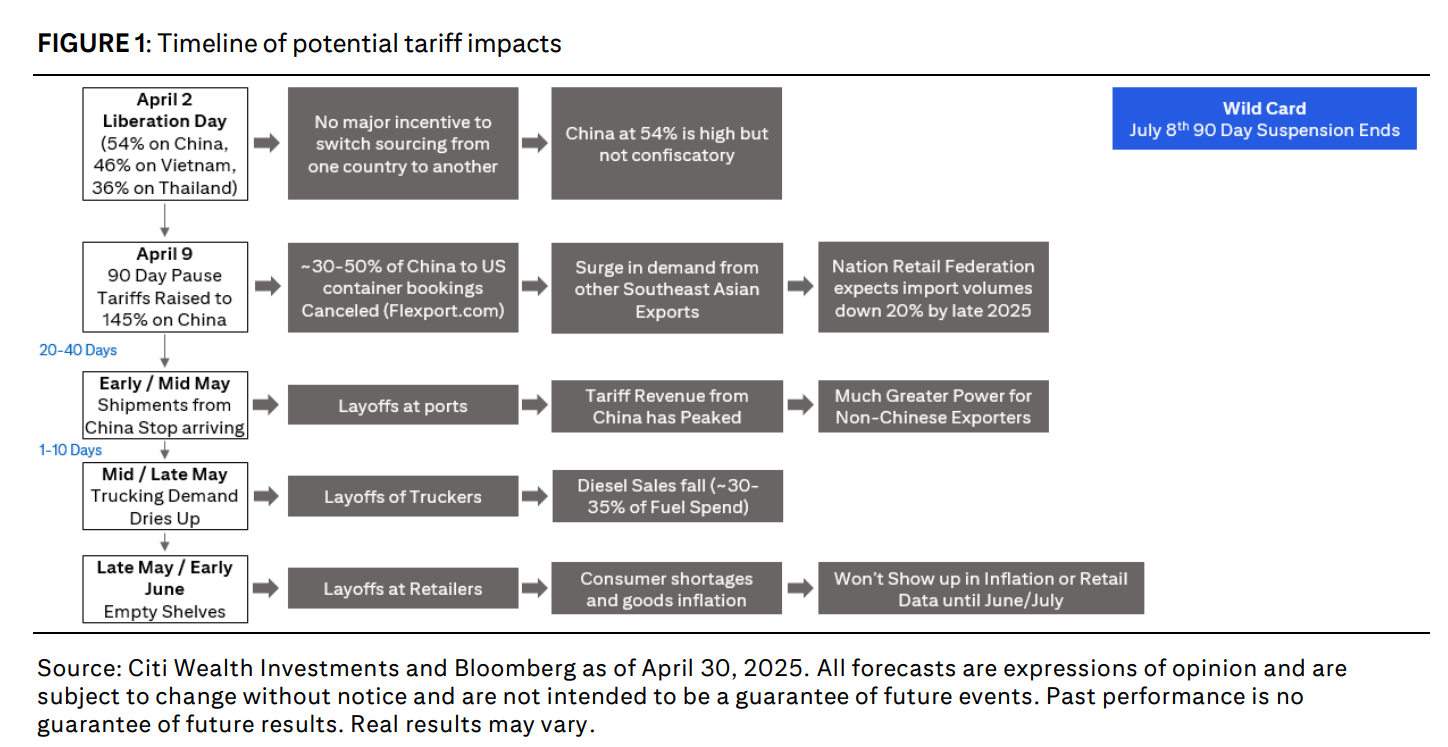

In the previous edition, I wrote a fair bit about the demand destruction that the tariffs are causing, which is leading to a sharp drop in incoming ships from China to the US. This is the first order effect of tariffs, and it's fairly obvious, i.e., tariffs are a tax that increases the cost of goods, which forces people to either defer or cancel their purchases. Given that the US imports the bulk of its goods, there will be a lower number of ships coming into the US ports because people are buying less.

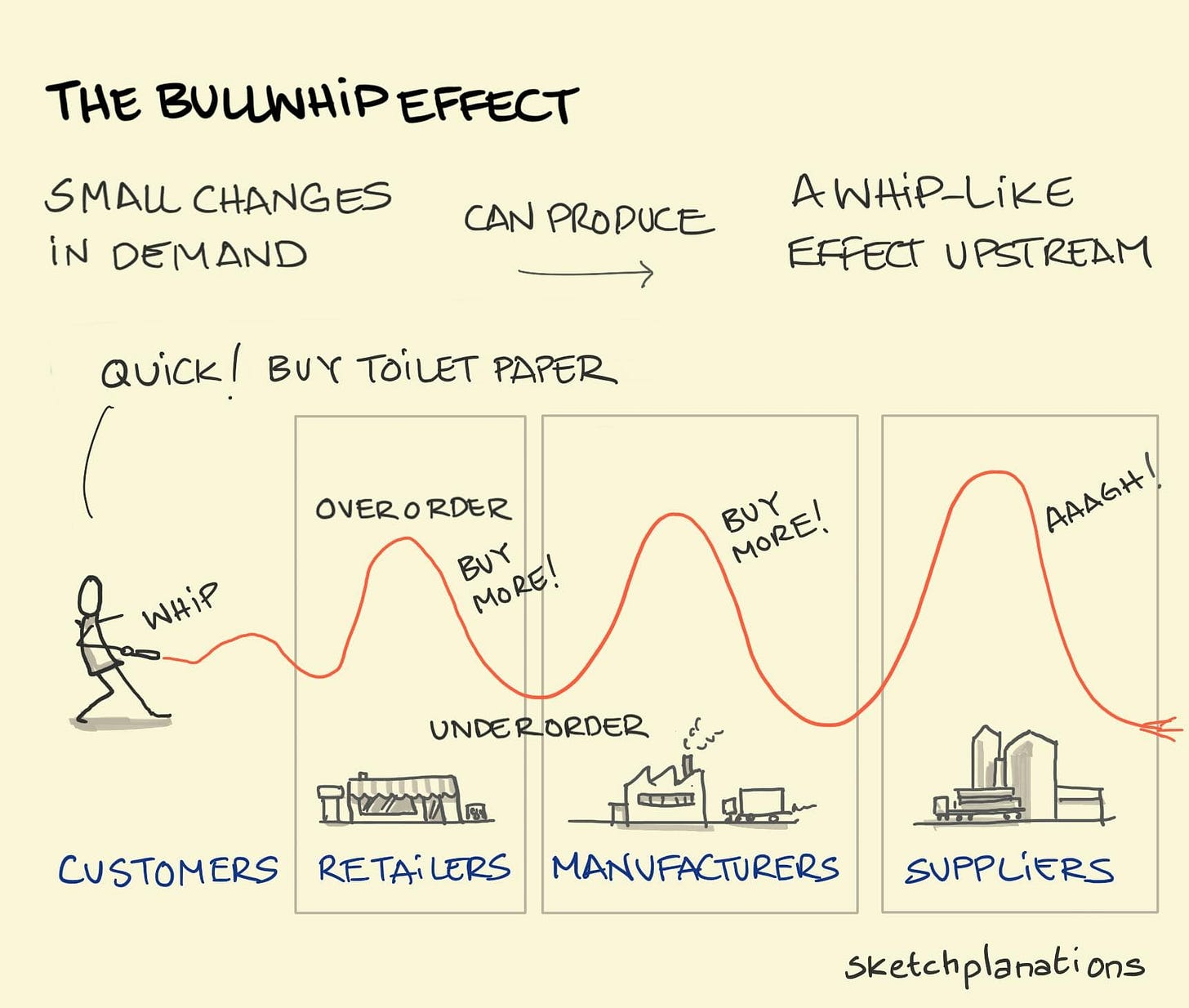

However, there are second-order effects that are far more costly. Right now, a lot of consumers and businesses are delaying their purchases until a deal is struck with China and tariffs are lifted.

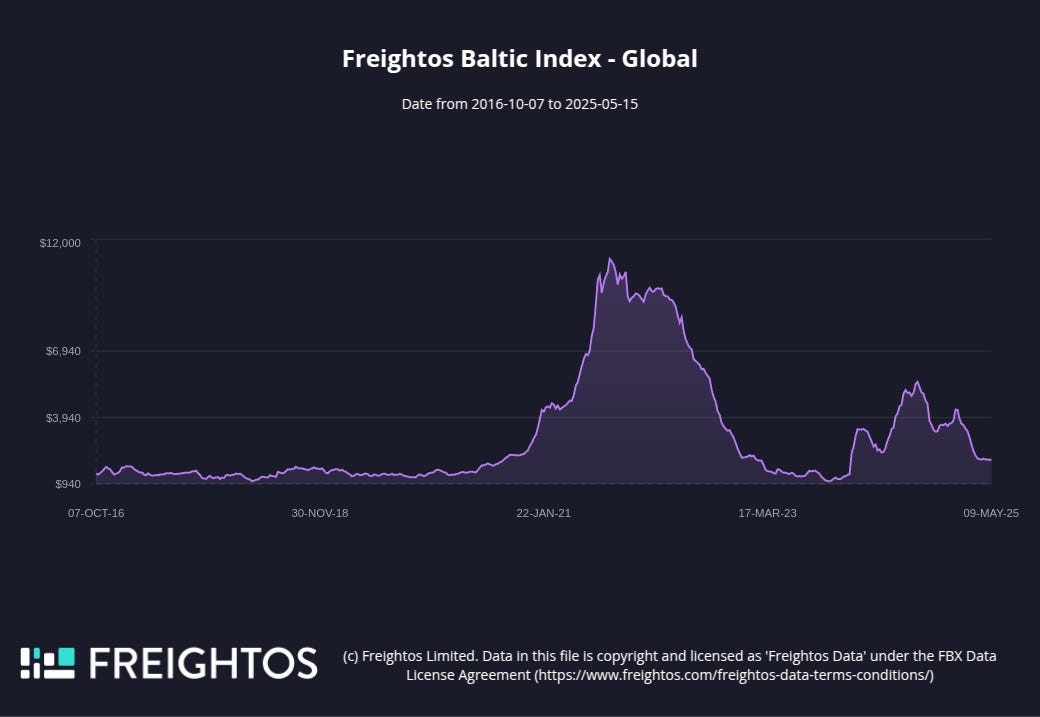

Once the tariffs are lifted, there's bound to be a sudden surge in ordering, which will push up the price of shipping. Shipping is not like software where you can "lagao server." Adding new ships or redirecting existing ships takes a long time. This is called the bullwhip effect, and the odds are we'll see one again.

The other side of all this change in demand and supply patterns is that there can be a shortage of containers. Right now, a lot of shipments that were supposed to head to the US are stuck in China in containers which means those containers are not in circulation. This is leading to a shortage of containers for Indian exporters which is pushing up freight costs for them while they are falling elsewhere.

Shipping costs are ultimately passed on by the manufacturers to the buyers. If the importer can afford to take a hit on the margins, they don't pass it on to the end consumers, otherwise, they do.

We saw all of this shipping drama in the aftermath of the COVID-19 reopening, which led to a massive demand and supply shock. This led to a sudden demand for ships and shipping containers, and there were massive backlogs of ships in ports, a shortage of containers, increased delivery time,s and a historic surge in shipping prices. We're likely to see this once again.

History doesn’t rhyme; it repeats.

All of this drama is because of the actions of one individual who was asleep during his elementary maths and econ class. Sigh!

Things are going great…

I was losing a lot of blood in my hand, so I chopped it off. Now, I am not losing blood anymore!

Donald Trump: "Well, I think certain aspects of it are. Costs, I was able to get down the costs, but even that, it takes a while to get them down, but we got them down good.

We lost $5 to $6 billion a day with Biden, $5 to $6 billion, and I've got that down to a great number right now in a very record time. You know, we're talking about 100 days. But just think of what that is, $5 billion a day we're losing on trade.

And we were very tough with China, as you know. We put a 145% tariff on—nobody's ever heard of such a thing—and we've essentially cut off trade relationships by putting that much of a tariff on. And that's OK.

We've gone cold turkey. That means that we're not losing, you know, we lost $1 trillion to China, $1 trillion. That means we're not losing $1 trillion when we go cold turkey because we're not doing business with them right now."

Revenge of the real

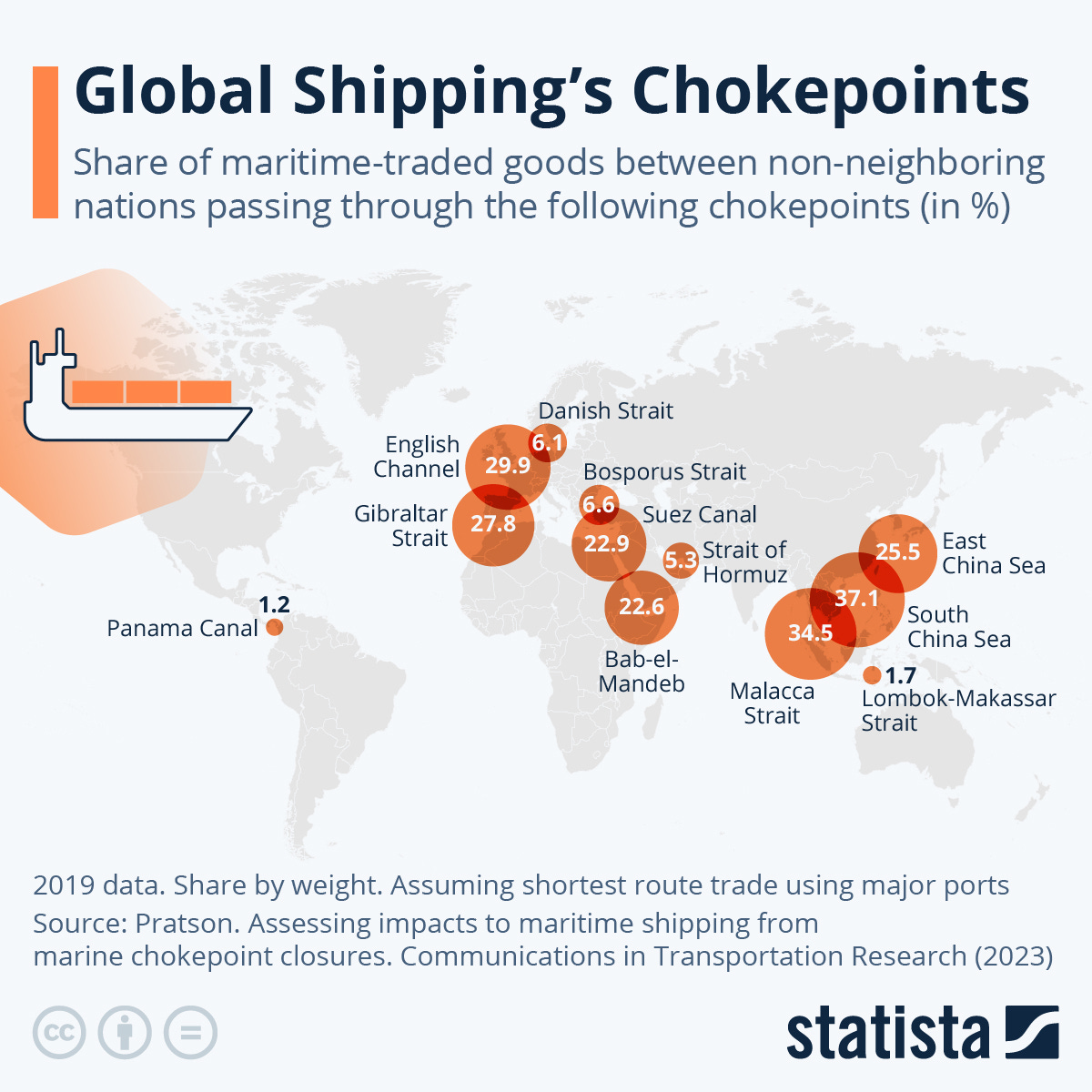

Last year, I heard Tim Sahay, who edits the phenomenal publication The Polycrisis, use the phrase "revenge of the real" on this podcast, and it stuck with me ever since. The context was all the crazy things that happened in the aftermath of the pandemic from breakdown of supply chains, droughts affecting shipping in the Panama Canal, the Houthis attacking ships that were entering the passageway to the Suez Canal, the dramatic increase in the price of commodities and so on i.e., real things having their revenge.

One particular episode of revenge taking, i.e., the Iran-backed Houthi fighters hitting ships passing through the Red Sea, had a disproportionate impact on the global economy. In normal times, ships would pick up goods from China and then enter the Bab al-Mandab Strait, pass through the Suez Canal, and then make their way to Europe. But the Houthis started attacking ships in response to Israel's military campaign in Gaza.

So now ships had to go all the way around Africa, which increased the time and cost of the voyages. The number of ships taking this route fell significantly, and as of April 2025, 50% fewer ships were taking this route compared to pre-November 202,3 when the attacks started.

In response to the attacks on the ships, the US under Joe Biden launched a naval operation to protect the passageway, which was more or less a failure. When Trump took office, he approved a new operation and gave the US military 30 days to deliver results.

Well, after 30 days, 100 strikes, $1 billion spent, and the loss of several multi-million-dollar drones and fighter jets, Trump has pulled the plug on the operation. The deal is that the Houthis will stop hitting US ships in response to the US ending its military campaign against them. The Houthis have meanwhile said that they'll continue attacking other ships.

There seems to be a deeper reason for Trump stopping the strikes on the Houthis:

The immediate beneficiary of the apparent détente is Iran. Having parked the Houthi problem, Mr Trump looks closer than ever to a deal with the ayatollahs. Iran quickly declared it would resume a fourth round of talks within days. A draft agreement is said to be circulating that could see the Islamic Republic and America restore diplomatic relations after 45 years. If that materialises, technical teams would finalise a deal that lets Iran enrich uranium to low levels in perpetuity. Ahead of his trip to the Gulf on May 13th, Mr Trump has already let slip that “a very, very big announcement” is coming. “Things are moving very fast,” says an observer in touch with both the Iranians and the Americans.

Why am I talking about this?

By attacking ships in the Red Sea, the Houthis showed that they can cause a significant amount of economic disruption by disrupting an important node in the global economy.

This also marks the dangerous fusion of political grievances, geopolitics, economic security, and insurgency. It's not just countries that can disrupt key economic nodes but also other actors.

The Bab al-Mandab Strait and Suez Canal are what as known as chokepoints through which a significant amount of global trade passes. But they aren't the only ones, and there are several others that can be weaponized due to geopolitical tensions.

That extra moisture-absorbing Gucci underwear, which is right now keeping certain important anatomical parts in the southern regions of your abdomen, passes through one chokepoint at the very least.

Welcome to the age of weaponized interdependence.

Weaponized interdependence (WI) is defined as a condition under which an actor can exploit its position in an embedded network to gain a bargaining advantage over others in a contained system. In their 2019 International Security paper, Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman argue that WI challenges long-standing ways that international relations experts think about globalization.

States with political authority over central economic nodes “can weaponize networks to gather information or choke off economic and information flows, discover and exploit vulnerabilities, compel policy change, and deter unwanted actions.” This formulation compels scholars and practitioners alike to think differently about foreign economic policy, national security, and grand strategy for the twenty-first century.

This is a theme I want to explore further in future issues. I’ve written about this a couple of times in the past, but there’s more.

Moron risk premium

In 2022, Liz Truss became Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and appointed Kwasi Kwarteng as Chancellor. Kwasi Kwarteng then unveiled a mini-budget that contained a series of income tax cuts and corporate tax cuts—the largest tax cut package since 1972, all to be funded by increased government borrowing.

This immediately sparked a rout in the currency and bond markets with the 30‑year gilts rising by more than 1% in two trading days. The surging yields triggered a cascade of margin calls in defined‑benefit schemes that were using leveraged liability‑driven‑investment (LDI) strategies.

The forced sale of gilts to meet margin calls triggered more margin calls and funds dumped gilt bonds to raise cash, pushing yields still higher in a self‑reinforcing spiral.

During this mini crisis, Dario Perkins, managing director for macro at the research firm TS Lombard coined the "moron risk premium" to describe the extra yield investors began demanding on UK government bonds due to the reckless policies of Liz Truss.

Right now, investors in US bonds are starting to demand their own "moron risk premium" although not quite to the extent of the UK episode…yet.

The other way of visualizing the moron risk premium is in the divergence between dollar and treasury yields in the aftermath of Retard Day.

Waiting for the poop to hit the table fan

Hard economic U.S economic data points like GDP, jobs numbers, and inflation are yet to show the impact of the tariffs, but we may soon start to see them:

Widely followed economic activity data such as the CPI, non-farm payrolls, and GDP are typically the cornerstones of any serious macroeconomic analysis. As we write just one month after a sharp hike in US tariffs, economic conditions as described by this “hard” economic data are now only useful to historians, as they reflect a break between a “pre-tariff” and “post-tariff” implementation.

Moreover, pre-tariff economic activity is likely to show higher growth due to a burst of inventory stocking and consumer purchasing ahead of perceived tariff impacts. In our view, more coincident consumer sentiment data such as from the University of Michigan – reflecting a collapse to levels not seen since CPI was printing 9% - may be a more accurate predictor of the economic scenario unfolding in the back half of 2025 should tariffs remain in place. — Citi Wealth

You get a sense of things by looking at what's happening in China, where manufacturing activity hit its worst level since 2023.

Here’s Neil Dutta of Renaissance Macro, who’s one of the most thoughtful observers of the US economy:

Put it together and I continue to see two risks.

First, it’s welcome that conditions are not collapsing, but underlying economic conditions are still cooling and while all slowdowns don’t end in recession, all recessions begin with a slowdown.

Second, the stock market has not yet internalized the risk of weaker economic data. April and May will be discounted because of the trade war. June data will likely show a rebound in activity as freight perks up and July will break the tie, so to speak. If markets can shrug off bad news this summer then maybe then we can ring the all-clear bell.

Until then, I’d stay cautious.

But, the impact of tariffs on the US economy and markets may be overstated:

The 90-day cut to U.S.-China tariffs shows a hard economic rule shaping policy: supply chains can’t be rewired quickly without disruption. That’s reflected in both nations’ explicit goal of avoiding economic “decoupling.” We still think tariffs will up inflation and hurt growth, with recession-like effects in coming quarters. Earnings estimates often suffer steep cuts when activity slumps. See the chart. Analysts have already cut forecasts for broad S&P 500 earnings growth from 14% in January to 8.5%, a slightly bigger drop than in an average year, per LSEG data. Yet the cumulative impact on overall 2025 activity may be more limited. The U.S. average effective tariff rate could land around 10-15%, we estimate, higher than at the start of 2025 but a more manageable economic disruption.

What's hard to figure out at this point is how a slowdown in the US will ripple out and affect the rest of the world.

The question is, what's the long-term impact of Trump's stupid trade war?

Brad DeLong wrote an insightful post recently in which he uses that frame of Brexit to think about the second-order effects of the stupid war, and I fully agree with it:

It is becoming increasingly clear to me: Suppose Donald Trump were to stand before the cameras tomorrow and say “never mind” to all of his proposed tariffs, export restrictions, and trade-war bluster. Suppose he were to retreat from the abyss with a mischievous grin. Suppose he were to declare it all a test. Suppose he were to do all of that. Then the odds are the damage would have already been done, for we would still be living in a post-Trumpxit world.

What is Trumpxit? It is the rupture—already well underway—of the critical trust that undergirded the United States’ place at the heart of the global economy.

The term echoes Brexit, that act of political and economic self-harm that sliced the UK off from its most important economic relationships. But where Brexit was a sudden break with Europe, Trumpxit is a break with the world—and its consequences may be just as severe, if not worse.

As Winkler stressed, Brexit has already cost the UK dearly: at least 10% of its potential output gone, apparently for good. Since the 2016 referendum, Britain's economy has gone from outperformer to also-ran—its growth, investment, and productivity all trailing that of the European Union it so bitterly left behind. What makes this especially galling is that for the first 16 years of the 21st century, Britain was one of the best performers of Europe, drawing capital, talent, and innovation with the confidence that came from being an English-speaking, rule-of-law, finance-friendly EU member. And then… the fall.

Burning point

That humanity is being slowly tandooried to death is an undeniable fact. Of course, some people don't believe it, but that doesn't make it any less true. Science doesn't give a shit about your feelings. The question always has been, can we get our act together in time and make the wholesale changes needed to stave off the worst of climate change? The answer so far, at least, has been a resounding no.

The other issue with climate change is the way it is framed. In this regard, we've suffered from a poverty of perspective and historical context. Our discussions of climate have been far too narrow, siloed, devoid of nuance, and ultimately unhelpful—we are talking about a planetary scale phenomenon after all.

I came across this article on The Breakdown, a new publication that explores the political economy of the ecological crisis. The article was part of the inaugural edition and situates both the climate crisis and the actions and solutions that we have come up with in a broader context that is remarkably helpful.

A few important points from the article:

Climate change is a planetary-scale problem, and it is precisely at the planetary scale that we have no capacity to act.

Liberal capitalism is the dominant political and economic ideology of our times and its adherents suffer from a serious case of tunnel vision. The liberals have and still treat the climate crisis as a "market failure" that can be fixed if we just find the right levels on the market dials. It must be noted that this "market-oriented" thinking is the same among moderate libertarians.

We also seem to have embraced the belief that if the climate crisis gets worse because we fail to get our act together, the wealthy and powerful will eventually step in to save the planet out of self-interest. This has proven to be false. The rich are building underground bunkers, private walled-off cities with private militaries. They don't care about the poor.

Despite the rise of right-wing and populist politicians, they haven't broken off from the neoliberal consensus. They are doing the same thing, i.e., tax cuts, deregulation, privatization, etc, while railing against climate action and "the mainstream."

Perhaps my favorite passage was this:

Climate change has always had a scale problem. This is true in both the physical and the temporal sense. Unlike many other objects of knowledge and political struggle, climate change is widely understood as a global problem first, with second order (if by no means minor) impacts at smaller scales. The general sense is that its overall reality is planetary, and its effects cascade down upon the sub-planetary worlds in which we live, generating a perceived mismatch between what must be done, and what can be done—in other words, it often seems like the “most important” scale is the one at which we have no capacity to act.

The reason why this stood out to me was that I had heard this talk by the historian Nils Gilman in which he makes the same argument.

Here’s a snippet from the talk:

So the planetary is best understood in contradistinction to the global.

The global that we understand from globalization refers to things that flow around the world that humans move intentionally: money, goods, services, people, ideas. These are all things that humans intentionally move around the world, and we have a variety of governance institutions and systems that have been set up over the last—especially—75 years to manage those things. They don't always work that well, but there are a whole series of institutions which are designed to try to address those things, rooted in the multilateral member state system centered on the United Nations system. So that's the current system we have for global governance.

The planetary refers to things that also flow around the Earth but aren't done so intentionally by human action. So things like viruses, things like the carbon cycle, the nitrogen cycle, space junk that's floating around the earth—these are things that humans are affecting, and in some cases redirecting or creating, but unintentionally. And that flow regardless or irrespective of the borders—the human borders—that have been set up.

So globalization is about arbitrage—moving things between different places in the world in order to make a profit. These other things, these planetary phenomena, are not about arbitrage. They just flow irrespective of the borders, and we don't really have any effective institutions for dealing with those things."

US vs China and great power competition

The US vs China battle for supremacy is the defining rivalry of our times. It's number 1 vs number two, and it's a battle for supremacy across economic, military and technological spheres. Many commentators have even explicitly started calling this a “cold war”. Many in the west are operating under the assumption that a war between the US and China is inevitable and honestly, this scares the shit out of me.

This is a topic I'm deeply interested i,n and I've been trying to learn the history and also searching for frames to make sense of this rivalry. I recently watched an interesting talk on the topic by Michael Brenes, a Lecturer in History at Yale University and one of the authors of The Rivalry Peril about the book.

I wanted to share a few interesting insights from the talk:

The United States played a key role in enabling the growth of China after the Cold War. The US pushed for China to be integrated into the global economy, granting it the Most Favored Nation (MFN) trade status, and supporting China's incorporation into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in the early 2000s. The US hoped that it would bring China into the liberal international order, but this ultimately "backfired".

By 2011-12, Americans had grown tired of the endless wars, and support for the "War on Terror" had dwindled. At the same time, the American foreign policy establishment takes notice of China's rise, leading to the Obama administration's "pivot to Asia."

At the same time, even Chinese officials have started thinking that the US is in a long-term decline, especially after the 2008 global financial crisis. All three factors were the conditions in which the US-China rivalry arose.

The Democrats and Republicans have differing views of the rivalry. On the Democratic side, some think that rivalry can be managed, i.e., "competition without catastrophe". Others think that China wants to "displace the United States" as the leading global power, and this competition is a protracted conflict with no end in sight. The Republicans, on the other hand, are more aggressive in their views toward China and view this as a zero-sum conflict, i.e., we win, they lose.

I didn't know that the Biden administration used the China rivalry as a justification to spend money on the CHIPS Act and the Inflation Reduction Act.

“That shift may have been politically necessary. But it reduced bold domestic reform to Cold War-style military-Keynesianism—investing at home not for people’s welfare, but to defeat an external enemy.”

The idea of a "new Cold War" emerged during the first Trump administration. This hearkens back to the old Cold War. The popular conception of the Cold War is it was a "good vs. evil" struggle in which the US won against the Soviet Union, which ushered in an era of liberal democracy and capitalism.

Brenes argues that this view of the Cold War is flawed and ignores reality. The Cold War in Vietnam, Cambodia, and other parts of Asia was extremely bloody and violent. Back home in the US, the Cold War delayed civil rights reforms, opportunities for feminism, prevented programs like job guarantees or full employment bills, blocked projects viewed as too socialist or communist, and limited the expansion of the American welfare state.

The key argument that Brenes makes is that the US has embraced rivalry with China without understanding why or considering its long-term consequences. The competition has become an end in itself—"rivalry for the sake of rivalry"

The most important questions he raises:

Here’s what Van and I [Brenes] kept coming back to:

How do you win a competition with China?

What does “winning” even look like?

And if this is an enduring, unending conflict, what are the costs—for America, for democracy, and for the world?

We argue that the U.S. has embraced rivalry without a sober understanding of its long-term impacts. And that this approach is already destabilizing global peace—and weakening democracy at home.

So, apocalypse maybe?

Goddamn, I expected to read chaos and I got it but this is greatly researched and expressed beautifully, everyone seems to have their finger on the trigger

Really good one !!! so much useful info packed in here. chaotic but somehow kept me totally engaged haha. Waiting for the next read!